Joseph Wilson Swan was a British scientist with expertise in physics and chemistry. He created an effective light bulb that glowed using electricity. As a result, he played a significant role in popularizing electric lighting for homes and public spaces like theaters. One notable example of this is when his lights were used at the Savoy Theatre in London in 1881 to provide illumination.

In 1904, Swan received a great honor from King Edward VII. He was given a special award called the Hughes Medal by the Royal Society, and he became a member of an important group called the Pharmaceutical Society. Before that, Swan had been awarded the highest medal in France for his bravery during a visit to Paris in 1881. When he went there, many people saw his inventions on display at an international show about electricity. The whole city was even lit up with his special electric lighting.

Early Life of Joseph Wilson Swan

Joseph Wilson Swan was born in 1828 at a house called Pallion Hall in a place called Pallion, which is located in the Bishopwearmouth area of Sunderland, in County Durham.

He came from a family with his parents, John and Isabella Cameron.

Swan was trained by a pharmacy firm in Sunderland for six years, led by Hudson and Osbaldiston. Unfortunately, it’s unclear if he finished his training because both partners passed away after that time. As a kid, Swan had a curious mind and loved to learn more about his surroundings, the way people worked in the area, and what he read at the Sunderland Library. He also attended lectures at the Sunderland Atheneum to expand his knowledge.

After Swan joined Mawson’s, a chemical manufacturing firm based in Newcastle upon Tyne, he became a partner when he was just a teenager. The company was started by John Mawson, who had married Swan’s sister Elizabeth, on the year Swan was born. Over time, the company changed its name to Mawson, Swan, and Morgan before it closed down in 1973. Initially located on Grey Street in Newcastle upon Tyne near the famous Grey’s Monument, the building now houses a fashion store called END. Today, visitors can spot old-fashioned street lamps outside the store to remind them of the company’s past.

Swan lived at Underhill, Low Fell, Gateshead, in a big house on Kells Lane North. He did most of his experiments in the large greenhouse on the property. The house was later changed into Beaconsfield School, which is a private school that charges money for education. Students who went to this school could still see old electrical equipment that Swan had installed.

Light Bulbs Started Using Carbon Filaments In 1850, an inventor named Swan began experimenting with light bulbs that use thin strips of carbon. He placed these carbon strips in a glass bulb and removed the air from it using a special machine. However, his early light bulbs didn’t work very well because the machine didn’t remove enough air from the bulb. By 1860, Swan had created a working light bulb, but it didn’t last long because of its poor vacuum and electric source. In August 1863, he shared his design for a better vacuum pump with scientists at a meeting in London. This pump used mercury to trap any remaining air that needed to be removed from the system. Interestingly, Swan’s design was similar to another inventor’s pump called the Sprengel pump, and it came before Herman Sprengel invented it by two years. It’s also worth noting that Herman Sprengel made his discoveries while he was visiting London, which means he probably read about the work of scientists who shared their findings at meetings. Later, both Joseph Swan and Thomas Edison used the Sprengel pump to create better light bulbs with carbon filaments.

In 1875, Swan went back to work on the light bulb problem with some new tools. This time he used a better vacuum pump and a carbon thread that was made into a filament. The key thing about Swan’s improved lamp was that there wasn’t much air left in the tube where the filament was placed. This meant the filament could get very hot, almost white-hot, without catching fire. However, the filament didn’t have enough power to light up the bulb, so it needed thick copper wires to carry electricity through it.

Swan first showed off his new incandescent carbon lamp at a meeting for a group of chemists in Newcastle upon Tyne on December 18, 1878. But when he turned it on and it lit up brightly, it stopped working because the electricity was too strong. On January 17, 1879, Swan successfully showed off his lamp again, and this time it worked just fine. He had figured out a way to make incandescent electric lighting using a vacuum lamp. A few days later, on February 3, 1879, Swan demonstrated his working lamp to an audience of over seven hundred people at the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle upon Tyne. Sir William Armstrong was there to preside. After that, Swan started working on making a better carbon filament and finding a way to attach its ends. He came up with a way to treat cotton to make special threads, and he got a patent for his idea on November 27, 1880. From then on, Swan started installing light bulbs in homes and famous buildings across England.

A blue plaque honors Swan’s achievement in inventing the electric light bulb, as well as Underhill’s claim to being the first house globally to have electricity installed inside it. Located in Low Fell, Gateshead, this was the world’s first home with functioning light bulbs. On October 20, 1880, a lecture by Swan at the Lit & Phil Library in Newcastle’s Westgate Road made history as the first public room illuminated by electric lights. In 1881, Swan established his own business, The Swan Electric Light Company, which began mass production of electric light bulbs and started commercial sales.

The Savoy Theatre in London was the world’s first public building fully powered by electricity. A company called Swan provided about 1,200 incandescent light bulbs to illuminate the space. The power came from a large machine that generated 88.3 kilowatts of energy on land near the theater. The person who built the Savoy, Richard D’Oyly Carte, wanted to use electric lighting because it eliminated two big problems: bad air and heat. Gas burners produce both carbon dioxide and heat, which can be unhealthy for people watching a show. On the other hand, incandescent lights don’t consume oxygen and don’t make much heat either. However, the first generator wasn’t powerful enough to light up the entire theater at once. By December 28, 1881, only the front section of the building was lit electrically, while the stage still used gas lighting. But Carte wanted to show off the new technology safely and effectively. He stepped on stage with a burning bulb and showed everyone it wasn’t a fire hazard. Just one day later, The Times newspaper wrote that using electricity for lighting was much better than using gas because it looked more beautiful and clearer.

The very first private home that was lit with Thomas Edison’s new invention, the incandescent lamp, belonged to his friend Sir William Armstrong at his estate in Northumberland. Edison personally made sure everything was set up correctly there in December 1880. By then, Edison had created “The Swan Electric Light Company Ltd” which had a factory located in Benwell, Newcastle. This company started making the first commercially available lightbulbs by early 1881.

Swan’s carbon rod lamp and carbon filament lamp were not very practical because they had low resistance, which meant that expensive thick copper wires were needed to make them work properly. While Swan was trying to find a better way to light his bulbs, he accidentally made another important discovery. In 1881, he invented a method for squeezing nitrocellulose through tiny holes to create thin fibers that could conduct electricity. His new company (which eventually merged with Edison’s company) started using these special fibers in their light bulbs. The textile industry also took advantage of this invention and began using it to make different products.

The first ship to use Swan’s invention of incandescent lamps was The City of Richmond, owned by the Inman Line. In June 1881, this ship was fitted with these new lamps. Shortly after, the Royal Navy also started using them on its ships; one example is HMS Inflexible, which got the new lamps installed in the same year. An early job for Swan’s invention was during the construction of the Severn Tunnel, where a contractor named Thomas Walker put “20-candlepower lamps” in the temporary pilot tunnels that were dug out at the time.

Swan helped create one of the first safety lights for miners using electricity, showing his early model in Newcastle upon Tyne at a meeting of engineers who focused on mining and mechanics. This light needed to be connected to wires. Later that year, Swan introduced another design with batteries, which improved the lamps even more. By 1886, the Edison-Swan Company had made a lamp with brighter light than the old flame safety lights. But this new lamp was not very reliable and didn’t work well for miners. It took other inventors working on it for about 20 years before electric lights became widely used by everyone.

Edison & Swan United Electric Light Company, also known as “Ediswan,” was formed after Thomas Edison’s and Frederick de Morgan Swan’s independent work on incandescent electric lamps around the same time. Both Swan and Edison developed their first successful lamps in 1880, with Edison aiming to use his lamp as part of a bigger system: a long-lasting high-resistance lamp that could be connected in parallel to power his large-scale electric-lighting business. However, Swan’s early lamp design was not suitable for this purpose due to its low resistance and short lifespan. In Britain, Swan held strong patents, which led the two companies to merge in 1883 and create the Edison & Swan United Electric Light Company. The company produced lamps using a cellulose filament that Swan invented in 1881, while the Edison Company used bamboo filaments outside of Britain. Later, General Electric began making its own cellulose filaments based on Swan’s patents until they were replaced by General Electric Metallized (GEM) baked cellulose filaments developed by GE in 1904.

In 1886, Ediswan relocated its production to an old jute factory in Ponders End, North London. By 1916, Ediswan had built the first radio factory that made thermionic valves in the UK at Ponders End. Over time, this area and the nearby Brimsdown developed as a key place for making thermionic valves, cathode-ray tubes, and other important electronics items. Nearby parts of Enfield became a significant center for the electronics industry over most of the 20th century. In the late 1920s, Ediswan joined two big companies: British Thomson-Houston and Associated Electrical Industries (AEI).

A scientist named Sir Joseph Wilson Swan had an interesting discovery about photography. When he was working with wet photos, he found that heat made the silver inside the photo more sensitive. By 1871, he created a way to use dry photos instead, and used a special plastic called nitrocellulose in place of glass, which made taking pictures much easier. Eight years later, Swan patented a type of paper called bromide paper, which is still used today for black-and-white photos.

In 1864, an inventor named Swan developed a new method for creating long-lasting photos called carbon printing. This new technique included an extra step where the photo was transferred onto paper, which made it possible to take pictures with lots of shades of gray and black.

In 1894, Swan became a member of the prestigious Royal Society (FRS), and two years later in 1898, he took on the role of president of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. At that time, he was one of three special members of the organization, along with Lord Kelvin and Henry Wilde. Later in 1901, Swan received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Durham University. He also served as leader of the Society of Chemical Industry between 1900-1901. In 1903, he was chosen to be the first president of the Faraday Society. The next year, in 1904, Swan was honored with a knighthood and received the Royal Society’s Hughes Medal. Additionally, he became an honorary member of the Pharmaceutical Society. Finally, in 1906, he won the Albert medal from the Royal Society of Arts.

In 1945, the company that provided electricity in London remembered the inventor of the light bulb by naming a ship after him. This ship was called the SS Sir Joseph Swan and it was a big coal freighter with a cargo capacity of 1,554 tons.

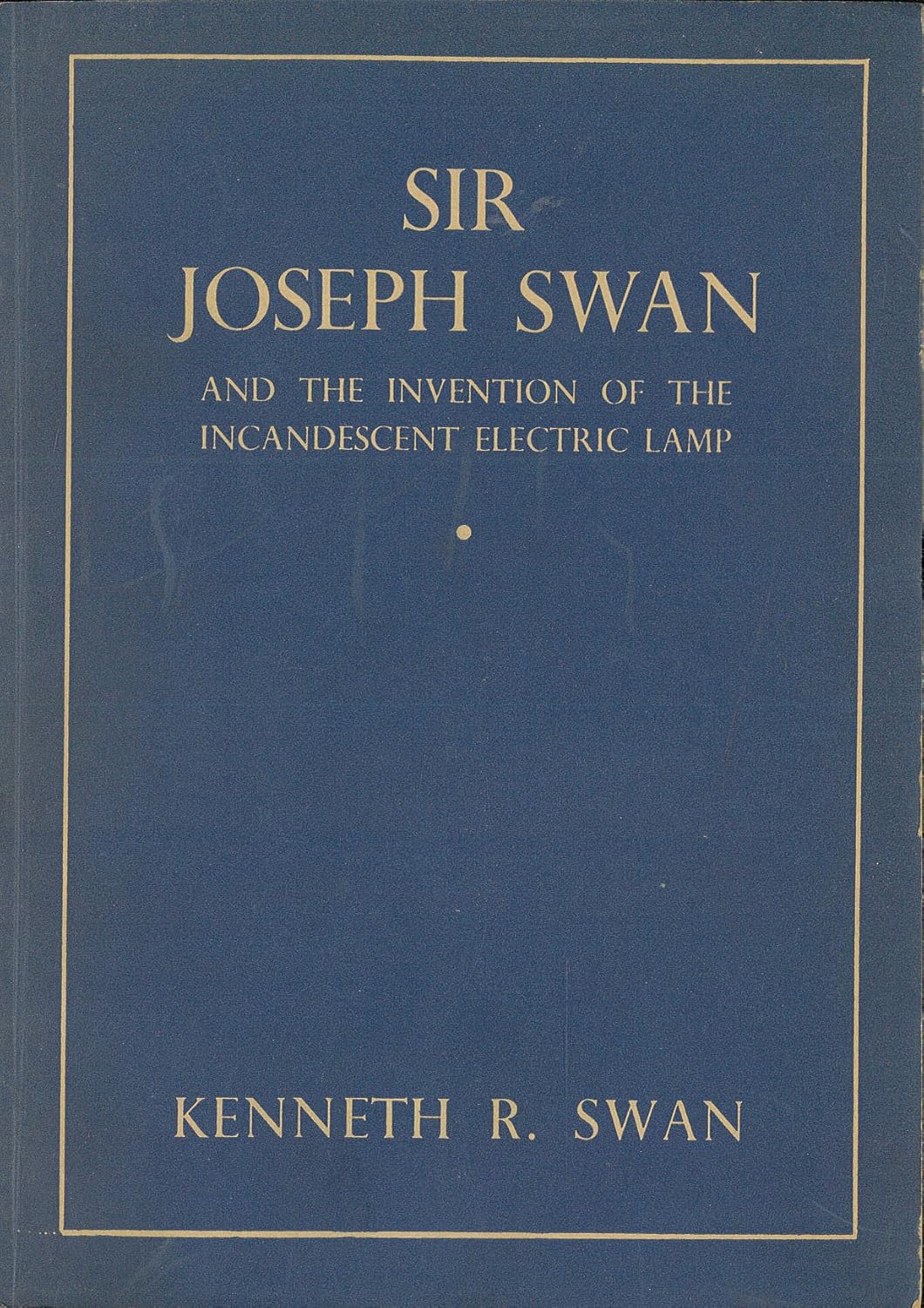

Sir Kenneth Rayden Swan’s personal life started with his marriage to Frances “Fanny” White in 1862 at Camberwell Chapel in London. They had three kids together, Cameron, Mary Edmonds, and Joseph Henry, who all survived them. Sadly, Frances passed away on January 9, 1868, and Sir Kenneth later married Hannah White, the younger sister of his late wife, in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, in October 1871. This time around, he welcomed five new children: Hilda, Frances Isobel, Kenneth Rayden, Percival, and Dorothy. As a lawyer with expertise in patent law, Sir Kenneth was well-respected in the community and an authority on his field of study.

Swan passed away in his home at Overhill in Warlingham, Surrey in 1914. His funeral service was held at All Saints’ Church in Warlingham on May 30, 1914, and he was buried in the churchyard. Many people who attended the ceremony were from important organizations such as the Institution of Electrical Engineers, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, and the Royal Society.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

- 19th Century (16)

- 19th Century Inventors (16)

- 20th Century (1)

- 20th Century Inventors (1)

Leave a Reply