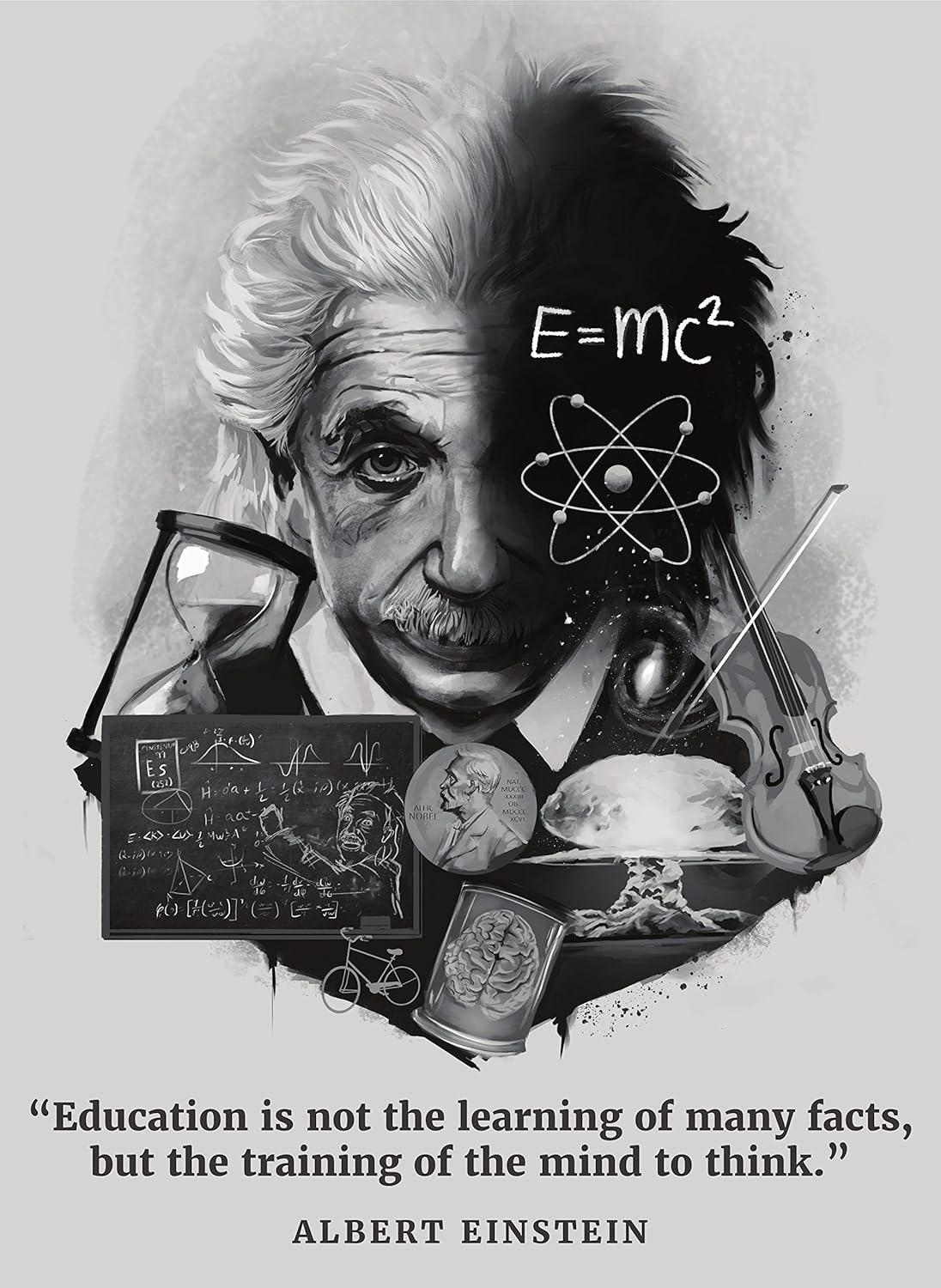

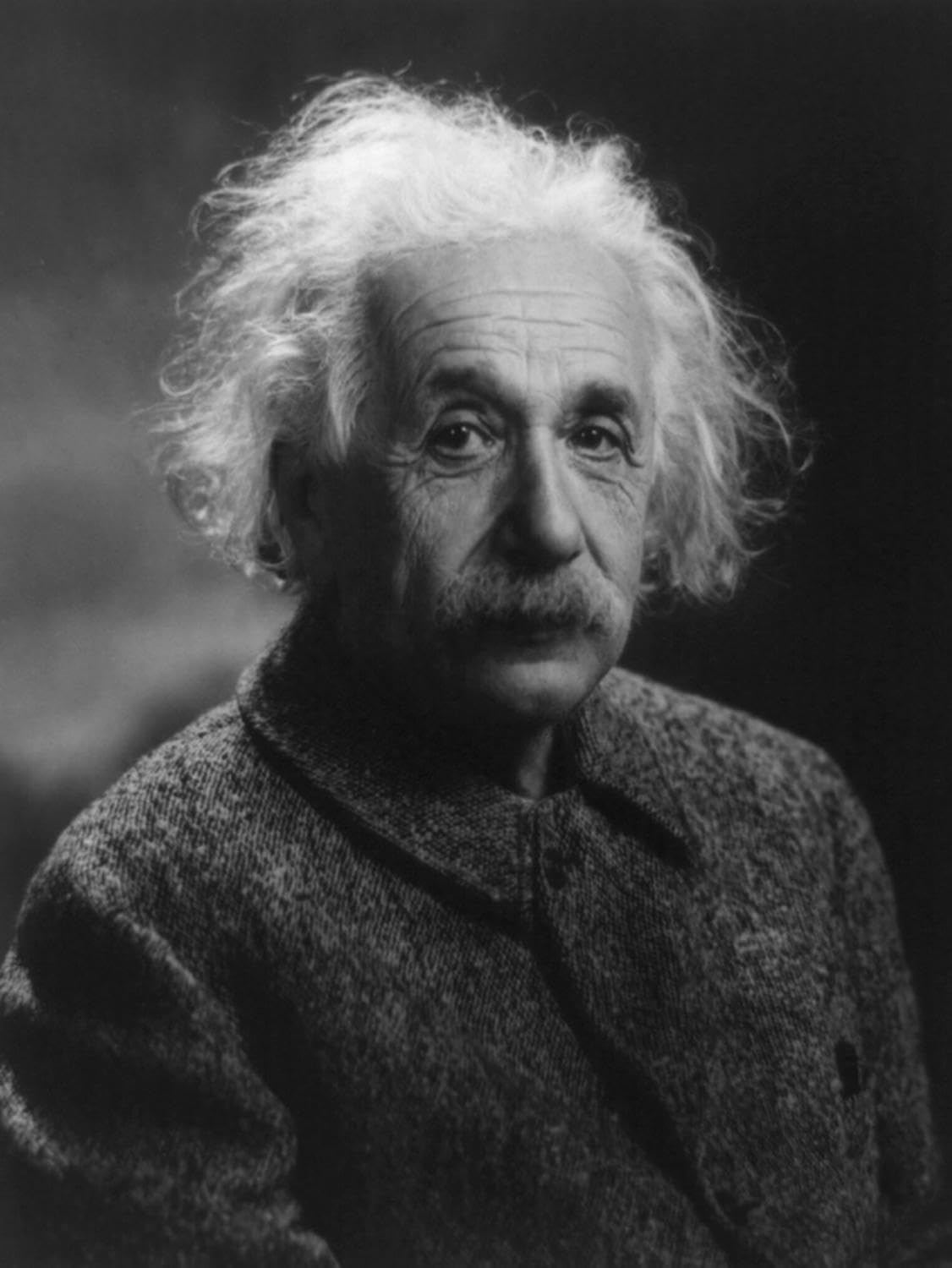

Albert Einstein was a brilliant physicist who was born in Germany on March 14, 1879, and passed away on April 18, 1955. He is most famous for creating a theory that changed how people understand space and time. Einstein also made big contributions to a field called quantum mechanics, which helps us understand really small things. One of his most well-known ideas is that anything that has mass also has energy, and this idea can be shown by the equation E = mc2, which is often called “the most famous equation in the world.” Einstein was recognized for his work with a special award in 1921, which honored his discoveries about how light behaves when it hits certain materials.

Born in the German Empire, Einstein moved to Switzerland in 1895 and gave up his German citizenship the following year. When he was 17 years old, he started studying at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich to become a math and physics teacher. He finished his studies in 1900. The next year, Einstein became a Swiss citizen. In 1903, he got a permanent job at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. A few years later, in 1905, he completed his PhD dissertation at the University of Zurich. By 1914, Einstein moved to Berlin and joined some important scientific groups. He also became a German citizen when he was part of the Kingdom of Prussia. In 1933, while visiting America, Adolf Hitler took power in Germany, causing Einstein to stay in the US. When Einstein realized that his Jewish friends were being treated unfairly by the Nazis, he decided not to go back home and got American citizenship in 1940. Before World War II started, Einstein wrote a letter to President Roosevelt warning him about a possible German nuclear project and suggested that the US start its own research on it.

In 1905, Albert Einstein made four important discoveries that are often called his “miracle year”. These papers explained how light behaves when it hits a surface and how tiny particles like dust move randomly in a fluid. He also introduced an idea about space and time that changed our understanding of gravity. This idea said that mass (like everything with weight) and energy are the same thing. The next year, Einstein came up with another big theory called general relativity. It helped us understand how the universe works by combining his ideas from before. In 1917, he wrote a paper that included some ideas that would later help create new technologies like lasers. Later in 1935, Einstein collaborated with physicist Nathan Rosen and came up with an idea about tunnels through space-time called wormholes.

In the middle years of his career, Einstein made significant advancements in statistical mechanics and quantum theory. One notable area of his work was the study of quantum physics of radiation, which showed that light is made up of tiny particles called photons. Along with physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, he helped create a foundation for a new kind of statistics known as Bose-Einstein statistics. For most of the later part of his academic life, Einstein worked on two projects that ultimately failed to succeed. First, he argued against the idea that quantum theory brings randomness into our understanding of the world, saying that God wouldn’t allow such unpredictability. Second, he tried to come up with a unified field theory by adding electromagnetism to his existing ideas about gravity and geometry. As a result, Einstein became less accepted by mainstream modern physics. In 1999, he was named Time’s Person of the Century.

Einstein’s Early Life and Childhood Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Germany, to parents Hermann and Pauline Koch. His family background was Jewish, and his father was an engineer. When Einstein was three years old, he moved with his family to a new home in Munich.

As a child, Einstein grew up surrounded by innovation and technology. His uncle Jakob had started a business that manufactured electrical equipment based on direct current. This exposure sparked Einstein’s interest in electricity and magnetism.

Einstein often talked about an event from his childhood when he was sick in bed and his father brought him a compass. He found it fascinating and wondered what made magnets attract each other. He felt like there must be something mysterious at work, which became a lifelong question that drove his curiosity.

Albert went to a Catholic school called St. Peter’s in Munich when he was just five years old. When Albert turned eight, he moved to another school called Luitpold Gymnasium where he got better and more advanced education that would help him learn even more in later grades.

Einstein’s parents, Hermann and Pauline, were involved in their family business, but they didn’t succeed in getting a contract to install electric lighting in Munich in 1894. The problem was that they didn’t have enough money to update their technology from direct current to alternating current, which is more efficient. Because of this failure, they had to sell their factory and look for other chances elsewhere. The Einstein family then moved to Italy, first to Milan and later to Pavia, where they settled in a house called Palazzo Cornazzani. At that time, Einstein was 15 years old, so he stayed behind in Munich to finish his schoolwork. His dad wanted him to study electrical engineering, but Einstein wasn’t very interested in this subject because he didn’t like the way the school taught it – they just repeated things over and over without letting students think creatively. Later on, Einstein wrote that this kind of teaching was not good for creativity at all. A letter from a doctor arrived at the end of December 1894, and it helped the authorities decide to let Einstein go, so he could join his family in Pavia. When Einstein was still a teenager, he wrote an essay called “On the Investigation of the State of the Ether in a Magnetic Field”.

Einstein showed a natural talent for physics and math from a young age, and quickly gained advanced mathematical skills that most people didn’t develop until much later. By the time he was 12, he started learning algebra, calculus, and geometry on his own; he made huge progress so fast that he even came up with his own solution to the Pythagorean theorem by the time he was 13. A tutor named Max Talmud said that not long after giving Einstein a math book, the boy had finished reading it all by himself. This inspired Einstein to focus on more advanced math. Before long, Einstein’s math skills were so impressive that I couldn’t keep up with him. Einstein later said he had already mastered two important math subjects – integral and differential calculus – when he was just 14. He loved solving math problems and thinking about how they worked, and by age 12, he was convinced that the world could be understood through math.

When Albert Einstein was 14 in 1893, his interests had grown wider and included music and philosophy. At this age, he got introduced to Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason by Talmud. As it turned out, Kant became Einstein’s favorite philosopher. Interestingly, at just 13 years old, Einstein found Kant’s complex works easier to understand than most people would at a similar age.

In 1895, when he was just sixteen years old, Albert Einstein sat for an entrance exam at a school in Zurich, Switzerland that would later become one of the best technical schools in the country. Unfortunately, he didn’t do well enough on the general part of the test to get in, but he excelled in physics and math. His principal advised him to keep trying, so Einstein went back to school for another year at a gymnasium in Aarau, Switzerland. There, he met his future wife Marie Winteler – it turned out they were meant to be! (Einstein’s sister Maja later got married to Paul, Marie’s brother.)

In 1896, Einstein decided to give up his German citizenship so he wouldn’t have to join the military when he turned eighteen. He received a great certificate that year for completing high school, and it said he was really good at lots of subjects, including physics and math. When he was seventeen, Einstein started studying to be a teacher at the same school he took an entrance exam from. Marie Winteler, who was almost two years older than him, got a job teaching in a different town called Olsberg, Switzerland.

Among the five other freshmen at the polytechnic school who were taking the same course as Albert Einstein, there was one woman, Mileva Marić, who was just twenty years old and from Serbia. Over time, Einstein and Marić spent many hours talking about their shared interests and learning more about physics than they did in class. In his letters to her, Einstein said that it was much more fun for him to explore science with her by his side rather than reading about it alone. As they continued to learn together, the two students became not only friends but also romantically involved.

Physicists studying history disagree about how much Marić contributed to Einstein’s groundbreaking work published in 1915. There is some proof that she might have been inspired by her scientific ideas, but there are also scholars who question whether her influence on his thoughts was really very important.

Marriages, friendships, and kids Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić were together. In 1912, they got married. Letters between Einstein and Marić that were found later told us about something important that happened to her family when she was young. Back in 1902, while she visited her parents in a town called Novi Sad, she had a baby girl named Lieserl. When she went back to Switzerland, the baby wasn’t there. Nobody knows what happened to her after that. A letter Einstein wrote in September 1903 said he thought the baby might have been given away for adoption or died when she was very little because of scarlet fever.

Einstein married Marić in January 1903. Later, their son Hans Albert was born in Bern, Switzerland, in May 1904. Their second child, Eduard, arrived three years later, in July 1910. In letters Einstein wrote to his wife before Eduard’s birth, he expressed his love for her as being misplaced and regretted the life he thought he would have had if he married another woman, Marie Winteler. He often thought of his wife with deep affection and felt unhappy because of it.

Einstein started a relationship with Elsa Löwenthal in 1912. She was both his cousin on his mother’s side and his second cousin on his father’s side. When Einstein told Marić about his affair, she became upset and moved back to Zurich, taking her sons Hans Albert and Eduard with her. The couple divorced in February 1919 after being separated for five years. As part of the divorce agreement, Einstein promised to give any Nobel Prize money he won to Marić if he received it; he achieved this two years later.

Einstein wedded Löwenthal in 1919. The following year, he started dating Betty Neumann, who was the niece of his close friend Hans Mühsam. Despite this new relationship, Löwenthal remained devoted to Einstein and accompanied him when he moved to the United States in 1933. However, a year later, in 1935, she was diagnosed with serious health issues affecting her heart and kidneys. Unfortunately, she passed away in December 1936.

In 1930, a collection of Albert Einstein’s letters published by Hebrew University in Jerusalem revealed that he had relationships with several other women beyond his wife Löwenthal. These included Margarete Lebach, an Austrian woman who was married, Estella Katzenellenbogen, the owner of a lucrative flower shop, Toni Mendel, a wealthy Jewish widow, and Ethel Michanowski, a prominent socialite from Berlin. During their time together, Einstein received gifts from these women even though he was still married to Löwenthal. After his divorce, Einstein briefly dated Margarita Konenkova, who some believed might be a Russian spy. Her husband, Sergei Konenkov, a skilled sculptor, created a bronze bust of Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

After a severe mental health crisis when Einstein was around twenty years old, his son Eduard was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia. For the rest of his life, he mostly lived with his mom or was temporarily placed in an asylum. After she passed away, he was permanently admitted to Burghölzli, the main psychiatric hospital in Zurich.

1902-1909: Einstein worked as an assistant at the Swiss Patent Office.

Einstein finished his studies at the Federal Polytechnic School in 1900 and was qualified to teach math and physics. In February 1901, he became a Swiss citizen, but this didn’t lead to him being drafted into military service because the Swiss authorities thought he wasn’t healthy enough for it. Unfortunately, when Einstein looked for jobs at Swiss schools, they weren’t interested in hiring him either. He applied for a teaching position for almost two years before getting help from Marcel Grossmann’s father to get a job as an assistant examiner at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern.

Inventions and ideas that Einstein reviewed as part of his job at the patent office included designs for a machine that sorted gravel and an electric typewriter. His employers were happy with his work, but they didn’t think he was ready for promotion until he had “figured out all the latest technology”. It’s possible that his work on simple inventions helped him come up with his groundbreaking theory of special relativity. He developed these ideas by thinking about how signals travel and keeping clocks in sync – topics that also appeared in some of the gadgets he looked at.

In 1902, Albert Einstein gathered some friends he had met in Bern and started a group that got together regularly to talk about science and philosophy. They chose a name for their club, the Olympia Academy, which was kind of funny because it wasn’t very impressive. Sometimes, his friend Marić would join them, but she only listened carefully without saying much. The ideas they discussed were influenced by famous thinkers like Henri Poincaré, Ernst Mach, and David Hume, who all had a big impact on Einstein’s later thoughts and beliefs.

1900–1905: First Scientific Papers

In 1905, Albert Einstein presented two major scientific papers that set the stage for his future work. His first paper, “Effects of Capillary Phenomena,” was published in the journal Annalen der Physik in 1901 and introduced a theory of intermolecular attraction that he later discredited as useless. The same year, Einstein submitted his 24-page doctoral dissertation, “A New Method for Measuring Molecular Dimensions.” Although it wasn’t completed until April 30, 1905, the University of Zurich approved it three months later. After formal approval on January 15, 1906, Einstein received his Ph.D.

In 1905, four groundbreaking papers by Einstein made that year truly remarkable in the history of physics. These papers – on the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, special relativity, and mass-energy equivalence – greatly influenced physicists at the time.

1908-1933: Einstein’s Academic Life in Europe

Einstein’s job as a civil servant was coming to an end in 1908 when he got a part-time teaching job at the University of Bern. In 1909, he gave a lecture on special electricity and it impressed a lot of people, especially Alfred Kleiner. This caught the attention of the University of Zurich, which offered him a better job with more responsibilities as an associate professor. By 1911, Einstein was promoted to a full professor, where he accepted a chair at Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague. To do this, he had to become an Austrian citizen. Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to complete the process during his time there. During his stay in Prague, he wrote eleven important research papers.

In July 1912, Albert Einstein returned to his old school, ETH Zurich, where he would teach physics for a while. He focused on teaching thermodynamics and mechanics, and his main research areas were about how molecules work, how solids and liquids behave, and a new way to understand gravity that was based on how things move really fast. He got help with this part of the job from a friend named Marcel Grossmann, who knew more advanced math than Einstein did.

In the spring of 1913, two German scientists, Max Planck and Walther Nernst, visited Einstein in Zurich with an offer he couldn’t refuse – they wanted him to move to Berlin. They promised him a high-profile spot at the Prussian Academy of Sciences, a top job at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, and a chair at the Humboldt University of Berlin that would let him focus on his research without teaching duties. This was especially attractive because Einstein had recently met someone in Berlin named Elsa Löwenthal, who made the city an even more appealing place to live. He accepted their offer and joined the academy on July 24, 1913. A few months later, he moved into a new apartment in Berlin’s Dahlem district on April 1, 1914, and started his new job at Humboldt University shortly after.

In July 1914, the start of World War I marked the beginning of Einstein’s slow drift away from his homeland. When the “Manifesto of the Ninety-Three” was published in October 1914—a document signed by many famous German thinkers that supported Germany going to war—Einstein was one of the few German intellectuals who didn’t agree and signed a different, peaceful manifesto instead. Even though he expressed doubts about Germany’s actions, Einstein was still elected as president of the German Physical Society for two years in 1916. A year later, when the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics opened its doors, Einstein became its first director, just like Planck and Nernst had promised.

In 1920, Albert Einstein became a Foreign Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, and two years later, he joined as a Foreign Member of the prestigious Royal Society. By 1922, Einstein had been honored with the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to theoretical physics, particularly for his groundbreaking work on the photoelectric effect. However, some physicists still questioned Einstein’s theory of general relativity at that time, and even the Nobel citation expressed doubt about his concept of light as a particle. It wasn’t until 1924 that another scientist, S.N. Bose, proved the Planck spectrum, which solidified Einstein’s idea and won over the entire scientific community. That same year, Einstein was also elected an International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. For many years, Britain’s equivalent to the Nobel Prize, the Copley Medal from the Royal Society, had eluded him until 1925. Ten years later, in 1930, Einstein was welcomed as an International Member of the American Philosophical Society.

In March 1933, Albert Einstein stepped down from his position at the Prussian Academy. During his time in Berlin, he had achieved many notable successes. One of his most important accomplishments was completing the theory of general relativity, which proved a key concept known as the Einstein-de Haas effect. He also made significant contributions to the study of quantum radiation and helped develop a way to understand how particles behave, called Bose-Einstein statistics.

1919: Putting general relativity to the test was finally possible after years of work by Einstein and his team. A big event, the total solar eclipse on May 29, 1919, happened in two locations – Príncipe and Sobral. Scientists from different countries compared their observations and shared them with a group of experts in London who were part of both the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. They talked about what they found at a meeting that took place on November 6, 1919.

In 1907, Einstein made an important discovery to help him understand how gravity works better than before. He said that if someone was in a tiny box falling down inside a gravitational field, they wouldn’t be able to tell if the field is really there or not. This idea helped him figure out how much light from a star would bend when it passed close to the Sun in 1911. Later, he changed his calculation and came up with a new way of thinking about gravity using special math called Riemannian geometry. By late 1915, Einstein had finished working on this part of his theory and applied it not just to how light bends around objects but also to another strange thing that happens in the Sun’s orbit around Mercury – its path changes slowly over time.

The big solar eclipse happened again on May 29, 1919, and this time scientists could test Einstein’s new ideas. Sir Arthur Eddington and his team took observations of the eclipse and compared them with what Einstein had predicted. They got matching results which proved that Einstein was right. News of their discovery spread fast around the world and people were excited about this new idea in science. A famous newspaper called The Times wrote: “Revolution in Science – New Idea About the Universe – Old Ways Are Over.”

1921-1923: Dealing with fame after winning the 1921 Nobel Prize for Physics

After Eddington’s eclipse observations were widely shared in both scientific and everyday publications, Einstein became perhaps the world’s first famous scientist, a brilliant thinker who had changed the way physicists thought about the universe since the 17th century.

Einstein started his new life as a famous thinker in America on April 2, 1921. He was greeted warmly by New York City’s Mayor John Francis Hylan and spent three weeks giving talks and attending social events. Einstein spoke several times at Columbia University and Princeton, and in Washington, he met with people from the National Academy of Sciences at the White House. After returning to Europe through London, he visited famous British thinkers like Viscount Haldane. There, he met important figures in Britain’s scientific, political, or intellectual circles and gave a lecture at King’s College. In July 1921, Einstein wrote an essay called “My First Impression of the U.S.A.” where he tried to describe the American personality, similar to Alexis de Tocqueville in his book Democracy in America (1835). He described his American friends in very positive terms: What stands out when visiting is that Americans have a happy and optimistic view of life.

In 1922, Einstein traveled to the old world rather than the new one. He spent six months exploring Asia, visiting countries like Japan, Singapore, and Sri Lanka (which was then known as Ceylon). After his first public speech in Tokyo, he met Emperor Yoshihito and his wife at the Imperial Palace, where thousands of people gathered outside to catch a glimpse of him. Einstein wrote about his impressions of the Japanese people in letters to his sons, saying they seemed kind, smart, and appreciative of art. However, his private diary had different thoughts: he thought the Japanese needed more intellectual pursuits than artistic ones. His journal also mentioned his views on China and India, which were not very positive. Einstein said Chinese people seemed lazy and looked puzzled when compared to others. He was worried that they might eventually replace all other cultures. For him, thinking about it made him feel really sad.

When he visited Mandatory Palestine for the last part of his trip, he spent 12 days there under British rule after World War I. Sir Herbert Samuel, the head of the British government in Palestine, greeted him with great ceremony and even had a cannon salute performed. One reception he attended was so crowded that people got upset because they wanted to hear him speak. Einstein told them that he was happy to see Jews being recognized as a powerful force in the world.

In 1922, Einstein’s decision to travel to the eastern hemisphere meant he wouldn’t be able to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm that December. Instead, a German diplomat took his place at the traditional banquet and gave a speech praising Einstein not only as a brilliant physicist but also as a passionate advocate for peace. In 1923, Einstein spent two weeks in Spain, where he received another award – a membership in the Spanish Academy of Sciences. This honor was celebrated with a special diploma presented to him by King Alfonso XIII. During his trip to Spain, Einstein also got to meet another Nobel laureate, neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

Einstein was part of an important international group called the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, which was connected to the League of Nations from 1922 to 1932. For most of that time, except for brief periods in 1923 and 1924, Einstein joined this committee based in Geneva, which aimed to bring people who thought deeply about science, art, and learning together with their counterparts from other countries. However, Einstein was not chosen as a representative of Switzerland due to some secret deals made by two Catholic activists named Oskar Halecki and Giuseppe Motta. By convincing the Secretary General Eric Drummond to give up his spot on the committee for a Swiss thinker, they opened the door for someone else to take it – Gonzague de Reynold used this opportunity to promote traditional Catholic ideas from his position in the League of Nations. Other notable members of the committee included Einstein’s former physics teacher Hendrik Lorentz and the famous Polish chemist Marie Curie.

In March and April 1925, Einstein and his wife traveled to South America. They spent about a week in Brazil, another week in Uruguay, and a month in Argentina. This trip was suggested by Jorge Duclout and Mauricio Nirenstein, who got help from several Argentine scholars, including Julio Rey Pastor, Jakob Laub, and Leopoldo Lugones. The tour was made possible with the support of organizations like the Council of the University of Buenos Aires and the Argentine Hebraic Association. Some additional funding came from the Argentine-Germanic Cultural Institution.

1930-1931: Einstein’s US Tour

In December 1930, Albert Einstein returned to the United States for another important visit. He was invited to spend two months at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) as part of a research fellowship. Caltech wanted to minimize the media attention that had followed him during his previous trip in 1921, so they asked him not to accept any awards or give speeches like he used to when he visited America before. However, Einstein was willing to spend some time with his fans and let them meet him whenever they asked.

After arriving in New York City, Einstein was invited to many exciting places and events, including Chinatown, lunch with The New York Times editors, and a performance of Carmen at the Metropolitan Opera, where he received applause from the crowd upon his arrival. Over the next few days, he was awarded the keys to the city by Mayor Jimmy Walker and met Nicholas Murray Butler, the president of Columbia University, who called Einstein “the king of brains”. Harry Emerson Fosdick, the pastor of New York’s Riverside Church, took Einstein on a tour of the church and showed him a huge statue made just for him, right at the entrance. During his stay in New York, he also joined 15,000 people at Madison Square Garden to celebrate Hanukkah.

Einstein attended the Hollywood premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights in January 1931 with his friend Chaplin. After this event, Einstein went to California where he met Caltech president and Nobel laureate Robert A. Millikan. However, their friendship was difficult due to Millikan’s strong support for military actions that Einstein strongly opposed as a pacifist. During one of his talks at Caltech, Einstein expressed the concern that science often causes more harm than good.

Einstein’s dislike of war also led him to befriend famous pacifists Upton Sinclair and Charlie Chaplin. The head of Universal Studios, Carl Laemmle, showed Einstein around his studio and introduced him to Chaplin, who they quickly hit it off with. Chaplin invited Einstein and his wife Elsa over for dinner at his home, where he described how Einstein’s calm exterior hid a very emotional personality that fueled his incredible intellect.

City Lights, starring Chaplin, was set to debut in Hollywood soon, and the actor invited two special guests, Einstein and Elsa, to attend with him. According to Walter Isaacson, this event marked one of the most memorable scenes in the new era of famous people. Later, when Chaplin visited Einstein’s house in Berlin, he remembered the humble abode and a piano where Einstein had started working on his groundbreaking idea. Chaplin wondered if the piano was even used as firewood by the Nazis at some point.

In February 1933, when Einstein was visiting the US, he realized that he couldn’t go back to Germany because the Nazis were taking over under their new leader, Adolf Hitler.

In early 1933, while studying at American universities, Albert Einstein led an educational tour to California Institute of Technology in Pasadena for his third two-month visiting professorship. Around February and March 1933, authorities repeatedly visited Einstein’s home in Berlin due to his political views. In March, Einstein and his wife Elsa traveled back to Europe, only to find out that the German government had passed a law called the Enabling Act on March 23, which essentially made Hitler the ruler of Germany. As a result, they realized their trip wouldn’t work as planned. After hearing that Nazi forces had taken over their vacation home and seized Einstein’s sailboat, the couple arrived in Antwerp, Belgium on March 28. There, Einstein immediately went to the German consulate, surrendered his passport, and gave up his right to be a German citizen. The Nazis later sold Einstein’s boat and turned their family home into a place for young Hitler supporters.

When Einstein arrived in England on May 26, 1933, he brought with him a landing card that marked his entry into Dover, the final stop before heading to Oxford. In April 1933, Einstein learned about a shocking change in Germany’s government: they had passed laws that made it impossible for Jewish people to hold any official jobs, including teaching at universities.

As historian Gerald Holton explains, without much resistance from their peers, thousands of Jewish scientists found themselves forced out of their university positions and erased from the institution records where they used to work.

A month after his work was published, Einstein’s writings were among those targeted by the German Student Union during the Nazi book burnings. The propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels publicly stated that “Jewish intellectualism has come to an end.” A German magazine included him on its list of enemies of the German government with a warning that said, “he hasn’t been caught yet”, offering a $5,000 reward for his capture. In a letter to physicist Max Born, who had already left Germany for England, Einstein wrote, … I was shocked by how brutal and fearful those people were. When Einstein moved to the US, he described the book burnings as an impulsive reaction from people who rejected popular ideas and most of all feared the influence of individuals with independent minds.

Einstein was now homeless, unsure where he would settle down or work, and worried about the fate of many other scientists still trapped in Germany. Thanks to the help of the Academic Assistance Council, which was set up by British politician William Beveridge in April 1933 to protect academics from Nazi persecution, Einstein was able to escape Germany. He rented a house in De Haan, Belgium, where he lived for a short time before moving on. In late July 1933, Einstein traveled to England for about six weeks at the invitation of British politician Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, who had become friends with him over the years. Locker-Lampson invited Einstein to stay near his home in Cromer, Norfolk, in a secluded cabin hidden away in Roughton Heath. To keep Einstein safe, Locker-Lampson arranged for two bodyguards to watch over him; a picture of them guarding Einstein was published in the Daily Herald on July 24, 1933.

Winston Churchill met with Albert Einstein at Chartwell House on May 31, 1933. Locker-Lampson invited Einstein to introduce him to Churchill, as well as former Prime Minister Lloyd George and historian Austen Chamberlain. Einstein asked for their assistance in rescuing Jewish scientists from Germany. According to British historian Martin Gilbert, Churchill quickly agreed and sent his friend physicist Frederick Lindemann to find the Jewish scientists and place them in British universities. Later, Churchill noticed that after Germany had forced out its Jewish population, it lowered its technical standards, which put the Allies’ technology ahead of theirs.

Einstein later reached out to leaders from other countries, including Turkey’s Prime Minister İsmet İnönü. In September 1933, he wrote a letter asking for the placement of unemployed German-Jewish scientists. As a result of Einstein’s letter, a total of over 1,000 Jewish people were eventually helped by the Turkish government.

Locker-Lampson presented a bill to the British parliament to grant Einstein citizenship during a time when Einstein made many public speeches about the troubles happening in Europe. In one of these speeches, he strongly criticized how Germany treated its Jewish population, while also proposing a bill that would give Jewish people from Palestine the right to become citizens. During his speech, he said Einstein was like a “global citizen” and should have a safe place to stay in the UK for a little while. Unfortunately, both of these bills didn’t pass, so Einstein decided to take another offer: becoming a resident scholar at an institute called the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, US.

Albert Einstein was a prominent scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. In 1933, he gave an important speech about the value of freedom of thought to a large crowd at the Royal Albert Hall in London. The audience was extremely enthusiastic, as reported by The Times. Four days later, Einstein returned to the United States and started working at this prestigious research center. At that time, many universities in America, such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, had few or no Jewish professors or students because of laws limiting Jewish people on their campuses. These restrictions lasted until the late 1940s.

Einstein’s future plans were still unclear. He had received job offers from several European universities, including Christ Church in Oxford, where he spent brief stays from May 1931 to June 1933. During this time, he was given a chance to work on research projects for five years with a special scholarship called a “studentship” at Christ Church. However, by 1935, Einstein had made up his mind and decided it would be best for him to stay in the United States permanently and apply for citizenship.

Einstein’s connection with the Institute for Advanced Study lasted until his death in 1955. He was among the first four people chosen (alongside John von Neumann, Kurt Gödel, and Hermann Weyl) when it opened its doors. He quickly became friends with Gödel; they would often take long walks together, sharing their ideas about science. Einstein’s assistant, Bruria Kaufman, later went on to become a physicist herself. During this time, Einstein tried to create a unified theory of the universe and challenge the understanding of quantum physics, but he was unsuccessful in both attempts. From 1935 onwards, Einstein lived in Princeton at his home. The house where he lived has been recognized as a National Historic Landmark since 1976.

In 1939, a team of Hungarian scientists led by Leó Szilárd traveled to Washington to warn American authorities about the Nazis’ secret atomic bomb project. Their warnings were ignored. However, Einstein and Szilárd believed they had a duty to inform Americans that German scientists might be able to build an atomic bomb first, and that Hitler would likely use it if he could. To make sure the US was aware of this danger, Szilárd and fellow refugee Eugene Wigner met with Einstein in July 1939 to explain the possibility of atomic bombs. Although Einstein didn’t think about nuclear weapons before, he agreed to support their cause by writing a letter to President Roosevelt. He and Szilárd asked him to write to the president, urging America to start its own research into nuclear arms.

The letter that was sent is thought to be one of the main reasons why the United States started looking into nuclear weapons seriously just before it joined World War II. Einstein also used his connections with the royal family in Belgium and the queen mother to arrange a private meeting at the White House’s Oval Office. Some people believe that as a result of Einstein’s letter and his meetings with President Roosevelt, the US started racing against other countries to develop an atomic bomb using all its available resources to create the Manhattan Project.

For Albert Einstein, war was like a contagious sickness that needed to be fought against. He believed in standing up against wars and violence. When he signed the letter to President Roosevelt, some people thought it didn’t align with his peaceful views. However, before his death in 1954, Einstein explained this to his friend Linus Pauling: “One thing I did wrong in my life was signing that letter recommending atom bombs be made – but there was a valid reason for it; the Germans might make them too.” In 1955, Einstein and ten other smart people, including Bertrand Russell from Britain, wrote an important statement about the dangers of nuclear weapons. When Einstein passed away in 1955, he received a big honor after his death: being named as one of the first members of the World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS), an organization started by brilliant scientists and thinkers who wanted to use science for good, especially when it came to stopping the development of nuclear weapons.

In 1940, Albert Einstein became an American citizen. At that time, he was already established in his career at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He was very grateful for the freedom to express himself without any social restrictions he saw in Europe. This freedom allowed people to think and say what they wanted without worrying about getting hurt or ostracized. As a result, Einstein believed that this kind of environment would help people be more creative, something that he valued greatly from his childhood education.

In Princeton, Albert Einstein joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). There, he worked hard to make sure African Americans had equal rights. He thought racism was America’s biggest problem, something that was passed down from one generation to the next. During his time with the NAACP, Einstein talked to another important civil rights leader named W.E.B. Du Bois and was willing to speak up for him in court when he was accused of being a spy. When Einstein offered to support Du Bois by testifying on his behalf, the judge decided to drop the case altogether.

In 1946, Albert Einstein visited Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, a school that was historically black. At this college, he received an honorary degree, which made him one of the first white people to do so. It’s worth noting that Lincoln was the first university in the US to give degrees to African Americans; some famous alumni include Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall. During his visit, Einstein spoke about racism in America, expressing his intention to not remain silent on the issue. A person who knew Einstein from Princeton shared a story about how he had once paid for the tuition of a black student at the university. Einstein believed that as a Jew himself, he could understand and feel sorry for what African Americans might be going through due to discrimination.

Personal views Political views In 1921, Albert Einstein and his wife Elsa arrived in New York City. They were joined by prominent Zionist leaders such as Chaim Weizmann, Weizmann’s wife Vera Weizmann, Menahem Ussishkin, and Ben-Zion Mossinson.

In 1918, Einstein signed a key document that founded the German Democratic Party, a liberal group. Over time, Einstein’s views on politics shifted towards socialism and he criticized capitalism in his writings. He explained these views in essays like “Why Socialism?”. Einstein’s opinions about communism changed as well. In 1925, he said that communist leaders needed a better system of government, calling their rule “terrible” and a “great sadness for humanity.” Later on, Einstein softened his stance, praising the method used by communist leader Vladimir Lenin in a 1929 comment.

I want to pay tribute to Lenin, a person who gave up everything for the sake of fighting for social justice. I don’t agree with his approach, but one thing is clear: individuals like him play a crucial role in reminding us of our shared values and guiding humanity towards what’s right.

Albert Einstein shared his opinions and made judgments on various subjects that were not directly related to physics or math. He strongly believed in creating a global government with democratic principles that would limit the power of countries within a world federation framework. Einstein stated that he supports a one-world government because he thinks it’s the only way to avoid humanity’s most severe threat. By 1932, the FBI had compiled a secret file on Einstein, which grew to an astonishing 1,427 pages before his passing.

Einstein was very inspired by Mahatma Gandhi and they corresponded with each other. He thought Gandhi would be an important example for future generations. The first meeting took place on September 27, 1931, when Wilfrid Israel brought his Indian guest V. A. Sundaram to meet Einstein at his home in Caputh during the summer. Sundaram was a student of Gandhi and acted as his special messenger, which is where Wilfrid Israel met him while visiting India in 1925. When Sundaram visited, Einstein wrote a short letter to Gandhi, which Sundaram then delivered to him. Soon after, Gandhi replied with his own message. Although they couldn’t meet face-to-face like they had hoped, they were able to establish a direct connection through Wilfrid Israel.

Einstein played a key role in setting up the Hebrew University of Jerusalem when it opened its doors in 1925. Before that, in 1921, he was approached by Chaim Weizmann, who led the World Zionist Organization, to help raise money for the university. Einstein suggested creating institutions like an agriculture institute, a chemical institute, and a microbiology institute to combat diseases such as malaria that were affecting the country’s development. He also supported the establishment of an Oriental Studies Institute, where students could take courses in both Hebrew and Arabic languages.

Albert Einstein did not support the idea of an independent Jewish state. He believed that new Jewish immigrants in Palestine, known as Aliyah, should be able to live alongside the Arab people already living there. Despite this, Israel was formed without his help in 1948, and Einstein had only a small role in the Zionist movement. When Israeli President Weizmann died in November 1952, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion offered Einstein a ceremonial job as the country’s president. This offer came from Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Abba Eban, who explained that it showed great respect for Einstein as a Jew. Einstein felt deeply touched by the offer but was also sad and embarrassed because he couldn’t accept it.

Einstein’s views on spirituality and philosophy are worth exploring. At a speech he gave for the United Jewish Appeal in 1943, Einstein talked about how our generation has made great progress in understanding human knowledge. He believed that the search for truth and wisdom was one of humanity’s greatest strengths.

According to Lee Smolin, it was Einstein’s strong moral compass that contributed to his incredible achievements. What drove him was a desire to understand how the laws of physics could explain everything in nature in a coherent and consistent way. Throughout his writings and interviews, Einstein shared his spiritual perspective. He sympathized with the impersonal pantheistic God idea from Baruch Spinoza’s philosophy.

Einstein didn’t believe in a personal god who was concerned about human lives and actions – he thought that view was simplistic. However, he did acknowledge that he wasn’t an atheist. Instead, he preferred to call himself an agnostic or someone with deep religious beliefs but not necessarily bound by traditional dogma. Einstein wrote that there is a universal spirit at work in the laws of nature – one that is far greater than human capabilities.

This realization led him to believe that pursuing science could lead to a unique kind of spiritual experience, one that was humble and humbling.

Einstein was closely connected to groups in the UK and US that didn’t follow religion but instead focused on humanism and ethics. In the US, he joined the advisory board of the First Humanist Society of New York and became an honorary member of the Rationalist Association, which publishes a magazine called New Humanist in Britain. When celebrating the 75th anniversary of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, Einstein said that the idea of Ethical Culture was very important to him and reflected his own views on what makes life most meaningful and lasting. He believed that without a strong sense of ethics, it’s impossible for humanity to find true salvation.

In a letter written in German to philosopher Eric Gutkind on January 3, 1954, Einstein expressed his thoughts on God and religion. According to him, the word “God” represents human weaknesses and is linked to old, primitive stories contained in the Bible. No matter how complex or clever an interpretation might be, it wouldn’t change his point of view. For Einstein, all religions, including Judaism, are rooted in childish superstitions. What’s more, as a Jew who feels a strong connection to this faith, he believes that Jewish people don’t have any special qualities that set them apart from others. In his opinion, they’re not “chosen” because of their religion or heritage.

Albert Einstein had been interested in vegetarianism for a long time. He wrote to Hermann Huth, who was in charge of the German Vegetarian Federation, back in 1930: Although I couldn’t follow a completely vegetarian diet because of external circumstances, I’ve always believed in the idea behind it on a deeper level. For me, being a vegetarian is not just about looks or morals – it makes sense to me that eating plants would have a big positive impact on people’s overall well-being and happiness.

He didn’t start eating vegetarian food until later in life. In March 1954, he wrote in a letter: Right now, I’m not getting any fats, meat, or fish, but I feel great about it. It’s strange to think that humans weren’t meant to be meat-eaters.

Music played a big role in Einstein’s life from a young age. He discovered his love for music when he was still quite little, and it remained with him throughout his entire life. As he grew older, Einstein would often express his passion for music through his writings, sharing his thoughts on how music had influenced him.

If I weren’t a scientist, I think I would have become a musician. I often imagine myself playing instruments and creating melodies. My thoughts are filled with musical ideas and rhythms. Life feels more meaningful to me when I’m thinking about music. Music brings me the most happiness in life.

Einstein’s mother played the piano fairly well and hoped her son would learn to play the violin too. She wanted him to develop a love for music as well as become more connected to German culture. A conductor named Leon Botstein said that Einstein started playing when he was five years old. But at that age, Einstein wasn’t very interested in it.

At 13 years old, he stumbled upon Mozart’s violin sonatas, which led him to fall deeply in love with Mozart’s music and start taking lessons more enthusiastically. Einstein taught himself how to play without following any specific practice routine. He believed that when you’re passionate about something, it becomes easier to learn than if you were forced to study out of obligation. By the time he was 17, people at his school had heard him playing Beethoven’s violin sonatas and were impressed by his talent. The teacher who evaluated his performance later said that Einstein’s playing showed a remarkable understanding and insight into music. What really caught the teacher’s attention is that Einstein loved music deeply – a love that’s rare to find in students. Music held special meaning for this student, making it more than just something he learned in school.

Music became very important in Einstein’s life from this point forward. He never thought about becoming a professional musician himself, but he played with some experts, including Kurt Appelbaum, and even performed for people just for fun. Playing chamber music was also a regular part of his social calendar while he lived in Bern, Zurich, and Berlin. There, he would play with Max Planck and his son among other musicians. Interestingly, Einstein is sometimes incorrectly credited as the person who put together the 1937 version of Mozart’s music catalog; that work was actually done by Alfred Einstein, who might have been related to him.

In 1931, while working at California Institute of Technology, Einstein spent time at the Zoellner family music school in Los Angeles. There, he played famous pieces by Beethoven and Mozart with members of the Zoellner String Quartet. Later in his life, when a young quartet came to visit him in Princeton, he joined them on violin, and they were amazed by how good his playing sounded.

On April 17, 1955, Einstein suffered severe internal bleeding due to a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm that had been surgically repaired earlier by Rudolph Nissen in 1948. While he was at the hospital, Einstein carried with him a speech draft for a TV appearance honoring Israel’s seventh anniversary celebration, but unfortunately, he did not survive long enough to finish it.

Albert Einstein chose not to have surgery, stating that he wanted to leave on his own terms. It would be insensitive to artificially extend life by prolonging it. He felt he had contributed enough and believed it was time to move on. He planned to pass away with dignity. The next morning, Einstein passed away at the Princeton Hospital when he was 76 years old, continuing to work right up until the end of his life.

When Thomas Stoltz Harvey performed the autopsy on Einstein, he carefully took out Einstein’s brain for safekeeping, hoping that it would help future scientists figure out what made Einstein so smart. At the time of his death, Einstein’s family didn’t give their permission for this, but they thought it might be useful in understanding genius minds. After Einstein passed away, his body was cremated in Trenton, New Jersey.

In 1965, when J. Robert Oppenheimer gave a speech at the UNESCO headquarters to remember Albert Einstein, he shared his thoughts about Einstein’s personality. He said that Einstein was quite simple and didn’t have much knowledge about the world. However, there was something special about him – he was both very innocent and extremely stubborn.

Albert Einstein left behind many important things when he passed away. He gave all of his personal papers, books, and ideas to a special school in Jerusalem called the Hebrew University.

Scientific career Throughout his life, Albert Einstein was a prolific writer. He wrote many books and articles, totaling over 300 scientific papers and 150 non-scientific ones. In December 2014, universities and archives made public a huge collection of Einstein’s writings, including more than 30,000 unique documents. Besides working alone, Einstein also teamed up with other scientists on special projects like the Bose–Einstein statistics and the Einstein refrigerator, among others.

Statistical mechanics, thermodynamic fluctuations, and statistical physics are all connected concepts. The main article about these topics is found elsewhere. In 1900, Albert Einstein submitted his first paper to Annalen der Physik. It was about capillary attraction, which he published in 1901 under the title “Consequences of Capillarity Phenomena.” This paper discussed the results that could be obtained from studying how liquids interact with tiny tubes. Two more papers by Einstein were published between 1902 and 1903. They tried to understand how atoms behave using statistics instead of traditional methods. These ideas laid the groundwork for his next paper on Brownian motion in 1905, which provided strong evidence that molecules really do exist. In 1903 and 1904, Einstein’s research focused on how the size of atoms affects how they move in a mixture.

Einstein went back to studying thermodynamic changes in fluids at their critical point. Normally, the fluid’s density changes are controlled by taking the second derivative of its free energy with respect to its density. However, when the fluid reaches its critical point, this derivative becomes zero, causing huge changes in the fluid’s density. These changes affect light waves of all lengths, making the fluid appear milky white. Einstein connected this phenomenon to Rayleigh scattering, which happens when tiny changes are much smaller than the wavelength. He explained why the sky is blue using this effect, and he also figured out how critical opalescence works by studying the density fluctuations in matter.

1905 – A Year of Great Discoveries The four papers published by Albert Einstein in 1905 had a huge impact on modern physics. These papers covered important topics such as light and matter, time and space. They changed our understanding of how the world works and laid the foundation for many new ideas.

Einstein’s work was groundbreaking because it helped solve long-standing problems between two main ideas: electricity and mechanics. He figured out a way to make these two ideas work together by changing some rules about how objects move. These changes were only noticeable when things were moving really, really fast – almost as fast as light itself.

The new idea Einstein came up with later became known as the special theory of relativity. It was a major discovery that helped us understand more about space and time.

This study predicted that when observed from a moving frame of reference, a clock attached to a moving object would seem to run slower, and the object itself would appear shorter in its direction of movement. The paper also claimed that the concept of a luminiferous aether, which was one of the main ideas in physics at the time, was unnecessary.

In one of his most famous papers about how much energy is connected to mass, Albert Einstein came up with the equation E = mc2 as a result of his work on special relativity. Even though Einstein’s ideas from 1905 were initially disputed by many scientists, it eventually gained acceptance from leading experts in the field, starting with Max Planck.

Albert Einstein first explained his special theory of relativity by looking at how objects move. In 1908, a mathematician named Hermann Minkowski changed the way people thought about relativity. He showed that it was actually a way to understand space and time together as one thing. Later, in 1915, Einstein used some of Minkowski’s ideas to create his general theory of relativity.

General relativity and its equivalence principle were first introduced by Einstein between 1907 and 1915. This groundbreaking idea explains how we observe gravitational forces between objects as a result of massive objects warping spacetime around them. Over time, general relativity has become a crucial tool in modern astrophysics, helping us understand black holes – regions where gravity is so strong that even light can’t escape.

Albert Einstein believed that general relativity was developed because he didn’t think special relativity was perfect when it came to motion. He thought a theory that doesn’t favor any particular state of motion – not even an accelerated one – would be more logical. So, in 1907, Einstein wrote an article about acceleration under special relativity. In this article, titled “On the Relativity Principle and Its Conclusions”, he made a key point: for someone who is falling freely, the rules from special relativity still apply. This idea is called the equivalence principle. At the same time, Einstein also predicted some strange effects that happen when things are in strong gravitational fields.

In 1911, Einstein wrote another article that further explored how gravity affects the way light moves. This was a follow-up to his 1907 paper, which had made an educated guess about how much light bends around big objects. As a result, scientists could for the first time put general relativity’s predictions to the test with real-world experiments.

Gravitational waves were first predicted by Einstein in 1916. He said that these waves are like ripples in the fabric of space and time. They move outward from their source, carrying energy with them as a kind of gravitational radiation. This idea is based on general relativity’s concept of special speed limits for gravity. On the other hand, Newton’s law of gravitation says that gravity can travel at any speed, which doesn’t make sense in this case.

The discovery of gravitational waves began in the 1970s with observations of two neutron stars that were extremely close to each other, known as PSR B1913+16. Scientists realized that these stars were losing energy due to gravitational waves and it was causing them to move closer together faster than expected. This theory had been proposed by Albert Einstein decades ago, but the evidence wasn’t found until much later. The confirmation of Einstein’s prediction happened on February 11, 2016, when a team at LIGO released the first recorded observation of gravitational waves, which they detected on Earth on September 14, 2015, more than 100 years after Einstein had suggested it might be possible.

Karl Einstein’s theory of general relativity created some confusion about gauge invariance. As he worked on his ideas, Einstein developed an argument that made him think it was impossible to create a field theory based on general relativity. He stopped searching for equations that were completely unaffected by changes in measurement and instead looked for equations that would remain the same when transformed using any type of linear change.

In June 1913, a new idea called the Entwurf theory came about from these investigations. The name “Entwurf” means “draft,” so it was like an early sketch or proposal for a big theory. This draft idea was actually simpler and harder to understand than Einstein’s other famous theory of general relativity. It added some extra rules to help explain how things move, but still needed more work. Over the next two years, Einstein put in a lot of effort into this new idea. However, he later figured out that his “hole argument” was wrong and decided to start over with a new theory by November 1915.

The study of physical cosmology began to take shape in 1917 when Albert Einstein applied his theory of general relativity to the entire universe. By doing so, he found that his equations predicted a dynamic universe that was either getting smaller or bigger. At the time, there wasn’t enough observational evidence to support this idea, so Einstein introduced a new concept called the cosmological constant into his equations. This allowed him to modify the equations and predict a static universe. The modified equations suggested a universe with curved boundaries, which matched what Einstein understood about Mach’s principle at that moment. This model became known as the Einstein World or Einstein’s static universe.

After Edwin Hubble found out about the galaxies pulling away from us in 1929, Albert Einstein stopped believing in a static universe. Instead, he came up with two new ideas about how the universe works: the Friedmann-Einstein model and the Einstein-de Sitter model, which he introduced in 1931 and 1932 respectively. Both of these models did away with the concept of a special number called the cosmological constant, because Einstein thought it didn’t make sense theoretically.

Many biographies about Einstein make it seem like he thought his idea for the cosmological constant was a mistake in later years. This comes from a story where George Gamow supposedly got a letter from Einstein saying so. However, an astrophysicist named Mario Livio doesn’t think this really happened.

In 2013, a team led by Irish physicist Cormac O’Raifeartaigh found clues that showed Einstein was thinking about a steady-state model of the universe after learning about Hubble’s observations of galaxies moving away from each other. A previously unknown manuscript written by Einstein in 1931 revealed his ideas on how the expanding universe works, where matter’s density stays the same over time because new particles are constantly created to replace old ones. As Einstein explained, he was looking for a solution to a math problem that could match Hubble’s data and keep matter’s density steady: if you imagine a space with boundaries, matter keeps leaving it as particles escape. For the amount of matter to stay the same, more particles must be made inside the space from outside.

It seems clear that Albert Einstein thought about a model for an expanding universe where things stay the same over time many years before scientists like Hoyle, Bondi, and Gold came up with the same idea. But Einstein’s version had a major mistake in it, which he quickly realized and gave up on.

General relativity creates a dynamic space-time, making it hard to figure out how to identify conserved energy and momentum. A theorem called Noether’s theorem helps determine these quantities from a special kind of equation that describes motion invariance. However, because general relativity includes covariance, this invariance turns into a sort of symmetry. As a result, the energy and momentum calculated using Noether’s rules don’t form a true tensor due to this change.

Einstein believed that this was true for a fundamental reason: he could make the gravitational field disappear with certain coordinate choices. He thought that his non-covariant energy momentum description was actually the most accurate way to describe how energy and momentum behave in a gravitational field. Although some scientists, like Erwin Schrödinger, didn’t like using objects that weren’t coordinate-dependent, Einstein’s method has been supported by other physicists such as Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz.

Wormholes were developed in 1935 by Einstein and Nathan Rosen. They created a model called Einstein-Rosen bridges to represent tiny particles with electric charge as a solution to gravity’s field equations. This idea was part of a bigger project described in the paper “Does Gravity Play a Key Role in Creating Particles?” The models combined Schwarzschild black holes in a way that connected two different areas. Since these solutions didn’t rely on any physical object, Einstein and Rosen thought they could be the start of a theory that avoided tiny point-like particles. Unfortunately, later studies showed that Einstein-Rosen bridges aren’t stable at all.

Einstein-Cartan theory explained

Albert Einstein working at his office in Berlin University in 1920

To add spinning point particles to general relativity, the connection that helps us move around needed to be changed so it could include an extra part called torsion. This change was made by Einstein and Cartan in the 1920s.

The concept of gravity in general relativity is transformed into the idea that spacetime has curvature. When an object follows a curved path like an orbit, it’s not because an invisible force is pushing or pulling it away from its ideal straight-line path; instead, it’s trying to find its natural fall through space-time that’s warped by other massive objects present in it. A well-known phrase coined by John Archibald Wheeler illustrates this idea: The movement of matter influences the shape of spacetime, while the shape of spacetime guides how matter behaves. Einstein’s field equations describe how spacetime curves because of mass and energy distribution. The geodesic equation explains the opposite situation – how a freely falling object follows the straightest possible path in curved spacetime. Einstein believed this assumption was essential to complete his theory and considered it an independent idea that had to be introduced alongside the field equations. He thought that this part of the theory needed to be derived from the field equations themselves, rather than being presented separately. The non-linear nature of Einstein’s equations means that if you have a “chunk” of energy made only of gravitational forces – like a black hole – it would follow a trajectory determined solely by these field equations and not by any new laws. Therefore, Einstein proposed that the field equations should determine how a black hole moves on its own unique path, which is also a straight line in spacetime. Many scientists and philosophers have repeated the idea that the geodesic equation can be calculated by applying the field equations to objects with gravitational singularities, but this claim remains uncertain and disputed.

The old quantum theory explained that light behaves like tiny particles called quanta. When photons from this new light hit a metal plate, they could make electrons jump off and fly away.

Many years ago, in 1905, Albert Einstein thought that light was made up of small pieces – these “light quanta”. At the time, most scientists, including Max Planck and Niels Bohr, disagreed with him. It wasn’t until later, when Robert Millikan did some very precise experiments on how light affects metal plates, and Compton measured a different effect, that everyone finally agreed Einstein was right about his tiny particles of light.

Albert Einstein believed that each frequency of wave has a group of particles called photons with energy equal to hf, where h represents a special constant. He didn’t reveal much more information about this idea because he wasn’t certain how these tiny particles were connected to the wave pattern. However, he did think this concept would help explain some experiment results, particularly the photoelectric effect. Scientists later gave the name “photons” to these light quanta, which was introduced by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1926.

Quantized atomic vibrations began to take shape when Einstein came up with an idea for matter back in 1907. He thought that each atom in a lattice structure was like a separate violin string, vibrating independently and forming a series of regular sound waves. The problem was, it would be hard to measure the actual frequency of these vibrations, but Einstein still wanted to share his theory because it showed just how well quantum mechanics could help solve problems that had been puzzling classical mechanics for a long time. Later on, Peter Debye made some changes to this model.

In 1924, Albert Einstein got a description of a statistical model from Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose. This model used a counting method that assumed light was made up of tiny particles that couldn’t be told apart. Einstein thought this idea worked for some atoms too and sent his translation of Bose’s paper to the Zeitschrift für Physik journal.

Einstein also wrote his own articles about the model, including the idea that when things got really cold, these tiny particles would come together in a special state called a condensate. It took until 1995 for scientists Eric Allin Cornell and Carl Wieman to actually make this happen using super-cool equipment at their lab.

Now, we use Bose-Einstein statistics to explain how groups of particles that follow certain rules will behave when they get really cold or move around together. Einstein’s drawings for this idea are on display in a special archive at Leiden University library.

Einstein’s career didn’t take off until he was promoted to Technical Examiner Second Class at the patent office in 1906, but he hadn’t given up on academic life. A few years later, in 1908, he became a Privatdozent at the University of Bern. In his work “The Development of our Views on the Composition and Essence of Radiation,” Einstein explored how light behaves when it’s quantified, as well as an earlier paper from 1909 where he explained that Max Planck’s energy units must have clear movements and act in some ways independently like tiny particles. This research helped create a new idea called photons and sparked the concept of wave-particle duality in physics. For Einstein, seeing this dual nature in light was proof that physics needed a fresh start and a more unified approach.

In his work from 1911 to 1913, Planck updated his old theory and introduced an exciting new concept called zero-point energy as part of his “second quantum theory”. This idea quickly caught the attention of Albert Einstein and his assistant Otto Stern. They assumed that molecules rotating back and forth had this special kind of energy, so they compared their theoretical calculations with real-world data on hydrogen gas. The numbers matched perfectly. However, when they shared their findings with others, they suddenly lost confidence in their own idea – zero-point energy didn’t seem as correct anymore.

Stimulated Emission in 1917, Einstein published an article about stimulated emission while working on relativity theory at Physikalische Zeitschrift. This idea explained how masers and lasers work by creating a process that makes light more likely to go into specific modes with certain numbers of photons rather than being released all together. The article revealed that according to Planck’s rules, this process should have consistent statistics if it happened in one mode over another empty mode. Einstein’s paper played a huge role in the later development of quantum mechanics because it was the first study showing that atomic transitions had simple laws instead of complicated ones.

Albert Einstein was familiar with Louis de Broglie’s ideas about matter waves, which initially sparked skepticism. Later, Einstein created another significant paper that utilized de Broglie’s wave theory to match Bohr and Sommerfeld’s quantization rules. This work would later motivate Erwin Schrödinger to write his 1926 paper.

Albert Einstein had a significant role in creating quantum theory, which he started working on with his 1905 paper about the photoelectric effect. However, after 1925, when the field of quantum mechanics developed further, Einstein began to express his dissatisfaction with it. He thought that the randomness and unpredictability in quantum mechanics might not be fundamental, but rather a result of other factors, like determinism. In fact, he said that God couldn’t possibly be “random” like humans are at a dice game. Throughout his life, Einstein continued to believe that quantum mechanics was still missing some important pieces, and that it wasn’t yet fully understood.

The Bohr-Einstein debates were intense discussions about quantum mechanics between Einstein and Niels Bohr, two of its most influential figures. These public disagreements took place in 1925 and are still notable today because they had a significant impact on the philosophy of science. The outcome of these discussions will continue to shape how people understand quantum mechanics.

The Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox remains a topic of debate among physicists because Albert Einstein never fully agreed with quantum mechanics. Despite recognizing its accuracy, he believed a more fundamental explanation for nature was possible. Over time, he presented various arguments to support this idea, but one of his most persuasive points came from a conversation with Niels Bohr in 1930. Einstein proposed an experiment where two objects are allowed to interact and then separated by a large distance. The quantum-mechanical description of the two objects is represented mathematically as a wavefunction. If we know the initial wavefunction that describes both objects before they interact, the Schrödinger equation can calculate the updated wavefunction after their interaction. However, due to something called quantum entanglement, measuring one object would instantly affect the wavefunction describing the other object, no matter how far away it is. Furthermore, choosing which measurement to perform on the first object affects what possible outcome could occur for the second object. Einstein argued that there should be no instantaneous connection between the two objects, as this would undermine our ability to distinguish one thing from another in physics. He also claimed that even though an action done to one object can’t instantly change its true physical state, the wavefunction representing it can’t be a complete description of reality.

In 1935, Albert Einstein collaborated with Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen in a paper that introduced the EPR paradox. This hypothetical situation involved two particles connected in such a way that their properties were linked together. Even if they were separated by large distances, measuring one particle would immediately reveal information about the other particle’s position or momentum without having to touch it. The scientists claimed that no action taken on one particle could instantly affect the other because this would imply faster-than-light communication, which is not allowed according to Einstein’s theory of relativity.

To support their argument, they proposed a fundamental principle: If we can predict with absolute certainty (100% accuracy) a physical quantity without disturbing the system in any way, then that quantity must have an actual value. Using this idea, they concluded that the second particle had definite values for both position and momentum before either was measured. However, according to quantum mechanics, it’s not possible to measure certain properties simultaneously, so the two particles can’t share simultaneous values for those qualities.

Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen reached a critical conclusion: The current understanding of quantum theory is incomplete and doesn’t fully describe reality.

In 1964, John Stewart Bell took his study of quantum entanglement to new depths. He figured out that if you measure two particles that are connected in this special way, then assuming the results depend on secret factors hidden inside each particle would lead to a math problem about how the measurements match up. This math problem was later called the Bell inequality. Bell then showed that the strange predictions of quantum physics actually go against this math rule. As a result, if you wanted to explain these weird effects with secret variables, those variables would have to be able to connect instantly no matter how far apart the particles ever get. Bell argued that because having secret variables would mean things happen faster than the speed of light, it solves the EPR paradox in a way that Einstein wouldn’t have liked.

Even though some people thought the argument was too tricky, Albert Einstein personally disagreed with it. However, this argument became one of the most important papers ever published in Physical Review. Scientists consider it a key part of developing how we think about information at a quantum level.

Einstein wanted to take his work on general relativity even further by creating a new theory that would explain gravity and electricity together as two parts of a single whole. In 1950, he wrote about this unified field theory in an article called “On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation” for Scientific American. He tried to figure out the most basic laws of nature, which impressed many scientists but didn’t lead to a breakthrough: one major flaw in his idea was that it couldn’t handle the strong and weak nuclear forces, which weren’t well understood until years after he passed away. Even though most experts now think Einstein’s approach to unifying physics was wrong, he started an important goal that his successors are still working on – trying to create a theory of everything.

Einstein also conducted some failed experiments in the past that didn’t lead to new discoveries. He explored concepts related to force, superconductivity, and other areas of study without success.

Working with other scientists was an important part of Einstein’s work. He was the guest of honor at a big meeting in Brussels called the 1927 Solvay Conference, where many of the top physicists from around the world came together.

In addition to his close friends and colleagues Leopold Infeld, Nathan Rosen, Peter Bergmann, and others who had worked with him for a long time, Einstein also teamed up with other scientists on specific projects.

Einstein–de Haas Experiment in 1908, scientist Owen Willans Richardson discovered that when the magnetic moment of an object changes, it can start to spin around. This phenomenon happens because of a rule called conservation of angular momentum and it’s strong enough to be seen in materials that are attracted to magnets. In 1915, Albert Einstein and his colleague Wander Johannes de Haas published two papers showing they had observed this effect for the first time. The experiment involved measuring how magnetization works by looking at how electrons in a material line up along the magnetic field’s direction. These measurements also helped scientists figure out which part of the magnetization is caused by the spinning motion and the movement of electrons around their atoms. The Einstein-de Haas Experiment was the only one conducted, recorded, and published by Albert Einstein himself.

A special item made by Einstein-de Haas equipment was given to the Ampère Museum in Lyon, France by Geertruida de Haas-Lorentz, the wife of de Haas and daughter of Lorentz, back in 1961. The museum had lost it a long time ago and found it again in 2023.

Einstein’s inventive work began in 1926 when he teamed up with his former student Leó Szilárd to create something entirely new – the Einstein refrigerator. This groundbreaking invention was unlike any other at the time because it didn’t have any moving parts and only used heat as its main energy source. Later that year, U.S. patent 1,781,541 was officially awarded to Einstein and Leó Szilárd for their amazing discovery. Unfortunately, it took a while for the invention to be made widely available for sale, but one of their other promising ideas was bought by a Swedish company called Electrolux.